“What is heritage?” is not a question likely to feature on the lips of many South Africans on 24 September, Heritage Day. This is despite children wearing traditional dress to school, or people putting on their Springbok jerseys or eating their boerewors rolls.

Supermarkets are advertising Braai Day, the South African National Blood Service is calling on people to donate towards South Africa’s national blood heritage (despite the oddness of this call, we all should donate blood) and the Apartheid Museum is advertising Heritage Month on its Facebook page.

In Ntabankulu, the AmaMpondo cultural and heritage festival has just held its annual event in celebration of Heritage Month. There is obviously a lot happening in the commemoration of Heritage Day (see #heritageday on Twitter), but it does not necessarily lead to any great introspection on the subject. Why is this the case?

There are two reasons. The first lies with history — a close relation to heritage. Heritage is generally defined as an acknowledgement of historical artefacts, practices and sites which should be preserved for the benefit of future generations. However, the past is a fraught subject for many South Africans.

In late 2015, democratic South Africa experienced a series of protests that began around the continued presence of the statue of Cecil John Rhodes at the University of Cape Town. By the end of the year, a wave of protest had broken out among university students across the country, drawing in most of its 23 institutions of higher education. The echoes of this movement are still being felt, even today in 2022.

Words like “legacy” and “history” receive prominent attention on social media, but are often linked to expressions of pain and wounds connected to the past. Often when people post about national heritage symbols, or statues or other symbols of commemoration, they link these to the psychological wounds caused by a lack of social transformation which should have followed the end of apartheid in the early 1990s. Increasing poverty for most South Africans is often expressed as a sense of betrayal in the recent past.

Second, heritage itself is a contested subject. Much of this contestation centres on who has the right to speak for whom in relation to elements of the South African past. Heritage, at least the way it is understood in South Africa, often pits the needs and rights of one community against another. There is considerable disagreement among various South African communities over whose heritage should be commemorated.

This is evident, for instance, in relation to the heritage of the gay rights movement. The organisation, Forum for Empowerment of Women, does important work and runs the Soweto Pride March which will take place on 24 September this year. As an organisation, though, it continually encounters hate and prejudice directed towards its constituency, despite the Bill of Rights including a clause supporting non-discrimination on the grounds of sexuality.

Even the South African state is selective in what heritage it likes to commemorate. Since 1994, the ANC-led government at the local, provincial and national levels has embarked on a number of heritage initiatives. These include Freedom Park in Tshwane and the Robben Island Museum in Cape Town, all billed as historical sites of importance to the nation.

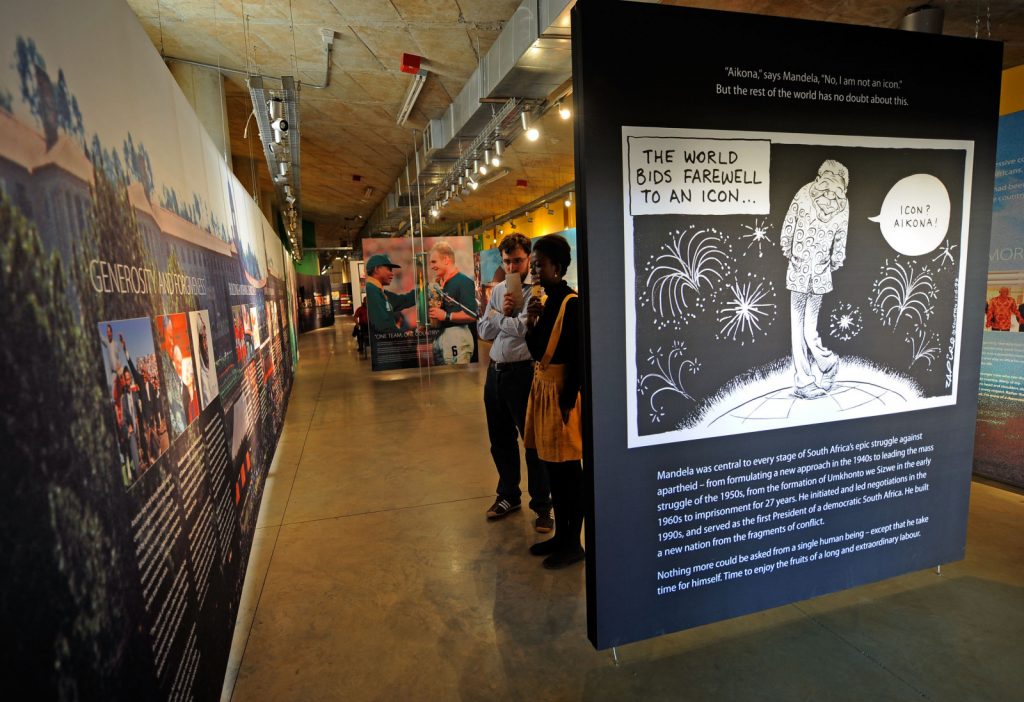

While national legislation defines heritage widely, most heritage initiatives commemorate the successes of the ANC in fighting against apartheid. Much of what is commemorated relates to events like the Sharpeville massacre in 1960 (where the participation of groups other than the ANC is not acknowledged), the Soweto uprising of 1976, and figures like Nelson Mandela. Alternatively, the ANC-led state emphasises the importance of preserving the intangible or living heritage of the African past, in the form of song and dance, or indigenous cultural practices.

Declaring something intangible like heritage is a neat move for a state reluctant to fund arts and culture — like theatre and provincial orchestras — even those that focus predominantly on indigenous musical traditions.

Further, state funding for heritage initiatives is also supposed to generate employment and local economic development. However, most national heritage sites do not generate profit. If anything, like Robben Island, they lurch from one financial crisis to another, dogged by poor management and faulty procurement processes. Especially after Covid-19, many of these facilities are in poor condition and struggle to deliver services.

The state’s approach to heritage is not one that finds favour with South Africans as witnessed by the recent outcry over a proposed R20-million flagpole. Where heritage projects claim to include community participation, ordinary people complain about lack of consultation and participation in local-government-run heritage projects. This is a common complaint about the Walter Sisulu Square of Dedication in Kliptown, Johannesburg.

National heritage production is paralleled by a series of initiatives represented in the privately-funded (or part-funded by the local and national government) community heritage initiatives. These projects challenge and subvert official authority about the past. Some of the better known ones include the District Six Museum and the Red Location Museum in Port Elizabeth.

Community heritage initiatives are also present in a range of public history projects, like the one centred on Alexandra in Johannesburg. Here, historians and heritage practitioners have encouraged residents to participate in a community history written from the bottom up to reflect ordinary people’s voices.

Many of these initiatives are truly excellent and well worth visiting (I don’t want to suggest that we shouldn’t commemorate our various heritages). However, community heritage museums and cultural centres have a tough time financially. The District Six Museum in Cape Town, for example, has continually struggled to raise funding. A current effort underway to build a Women’s Living History Museum in Pretoria is caught between the opposing impulses of the ANC, and the wishes of board members to acknowledge and commemorate all South African women, irrespective of political affiliation.

Across the country, museum curators and boards have had to balance the wishes of their funders with a sensitive approach to presenting community histories. Few heritage sites in South Africa, be they state-driven or private, expect to cover their running costs from income generated.

These issues — who may speak for whom and whose pasts should be represented (Coloured, Indian, black, white, men, women, gay, straight) — instead of being openly debated are concealed behind marketing promotions for boerewors or snoek curry, delicious though they are. It is not surprising then, that interest in a public holiday is high, but a general interest in heritage is at an all-time low.

Natasha Erlank is a professor of history at the University of Johannesburg.